Cross posting to original article posted here

How I scaled Machine Learning to a Billion dollars: Strategy

Cross posting here to original article I posted in https://medium.com/@analyticsaurabh/how-i-scaled-machine-learning-to-a-billion-dollars-strategy-2379faf86c02

Live Blog – day 4,5 – Dress recommendation models

<Please note that this post is unfinished because ************ even though we delivered better than expected results! Unlimited program went on to be 70% of revenue during my tenure>

This post is probably what you expected this series to be.

Previously, on building a production grade state of the art recommendation system in 30 days:

Live logging building a production recommendation engine in 30 days

Live reco build days 2-3 – Unlimited recommendation models

We had to get that work out of the way before can play. Let’s talk about the two baseline models we are building:

Bayesian model track

To refresh your memory, this simple Bayesian model is going to estimate

P(s | u) = P(c | u) * P(s | c)

where u is a user, s is a style (product in RTR terminology) and c is a carousel.

Well, what is c supposed to be?

Since we want explainable carousels, Sean is chasing down building this model with product attributes and 8 expert style persona tags (minimalist, glamorous, etc). We have a small merchandising team and tagging 1000 products with atleast 10 tags each took a month. To speed things up, we are going to ask Customer Experience (CX), a much larger team. They can tag all products within the week.

However, their definition of these style personas might be different than that of merchandising. So to start, we asked them tag a small sample of products (100) that had already been tagged. We got back results within a day. Then Sean compared how different ratings from these new taggers is compared to merchandising.

He compared them three ways. To refresh, ratings are from 1-5.

- Absolute mean difference of means of CX tags and original tags

-

- Average Difference is 0.45

- Mean Absolute Difference by Persona:

- Minimalist: 0.62

- Romantic: 0.44

- Glamorous: 0.24

- Sexy: 0.24

- Edgy: 0.37

- Boho: 0.35

- Preppy: 0.46

- Casual: 0.78

- Agreement between taggers of the same team

- CX tags cosine similarity to each other has median of 0.83, whereas original tags similarity to each other has median of 0.89. This is to be expected. Merchandisers speak the same language because they have to be specific. But CX is in the acceptable range of agreement.

- Agreement between CX tags and original merchandisers as measured by cosine similarity

- 99% above 0.8 and 87% above 0.9. So while they don’t match, they are directionally the same.

This is encouraging. Sean then set out to check the impact of these on rentals. He grouped members into folks who showed dominance of some attribute 3 previous months. Then tried to see what the probability of them renting the same attribute next month is. He computed chi squared metrics of these to see if they are statistically significant.

This is what you always want to do. You want to make sure your predictors are correlated with your response variable before you build a castle on top.

He found some correlations for things like formality but but not much else. He will continue into next week to solidify this analysis so we know for sure.

Matrix Factorization Collaborative filtering

This particular Bayesian model is attribute first. It says, given the attributes of the product, see how well you can predict what happened. These sort of models are called content based in literature.

I’m more on the AI/ML end of the data science spectrum, my kind is particularly distrustful of clever attributes and experts. We have what happened, we should be able to figure out what matters with enough data. I will throw in the hand-crafted attributes to see if that improves things, but that’s not where I’d start.

Please note that I do recommend Bayesian when the problem calls for it, or if that’s all I have, or have little data.

To be clear, the main difference between the two approaches is the Bayesian model we are building is merchandise attribute first. This ML model is order first. Both have to sail to the other shore but they are different starting points. We are doing both to minimize chance of failure.

This has implications on cold start, both new users and new products. It also has implications on how to name these products. So I walked around the block a few times and after a few coffees had a head full out ideas.

First things first, if we can’t predict the products, it doesn’t matter what we name the carousels. So let’s do that first. I had mentioned earlier that I had my test harness from when I built Rent The Runway recommendations, see here on github.

Matrix factorization is a fill-in-the-blanks algorithm. It is not strictly supervised or unsupervised. It decomposes users and products into the SAME latent space. This means that we can we can now talk in only this much, smaller space and what we say will apply to the large user x product space.

If you need a refresher on Matrix Factorization, please see this old post. Now come back to this and let’s talk about a really important addition -> Implicit Feedback Matrix Factorization.

We are not predicting ratings unlike Netflix. We are predicting whether or not someone will pick (order). Let’s say that instead of ratings matrix Y of, we have Z simply saying someone picked a product or didn’t, so it has 1s and 0s.

We will now introduce a new matrix C which indicates our confidence in the user having picked that item. In the case of user not picking a style, that cell in Z will be 0. The corresponding value in C will be low, not zero. This is because we don’t know if she did not do so because the dress wasn’t available in her size, her cart was already full (she can pick 3 items at a time), or myriad other reasons. In general, if Z has 1, we have high confidence and low everywhere else.

We still have

where is size num_users and num_categories and

is size num_products and num_categories.

But now our loss becomes

Let’s add some regularization

There are a lot of cool tricks in the paper, including personalized product to product recommendations per user, see the paper in all it’s glory here.

So I took all the users who had been in the program for at least 2 months for past two years. I took only their orders (picks), even though we have hearts, views and other data available to us. I got a beefy Amazon large memory box (thanks DevOps) and ran this few a few epochs. I pretty much left the parameters to what I had done last time around – 20 factors and a small regularizing lambda of 0.01. This came up with and

in 20 factor space.

This is a good time to gut-check. I asked someone in the office to sit with me. I showed her her previous history that the algorithm considered –

Then predicted her recommendations and asked her to tell me which ones she would wear.

For her, the results were really good. Everything predicted was either something she had considered, hearted, worn. There were some she said she wouldn’t wear but it was less than 10 products in this 100 product sample.

This is great news, we are on track. We still have to validate against all users to do a reality check of how many did we actually predict on aggregate. But that’s next week.

So now to the second question. How do we put these products into carousels? How do we cold-start?

Carousels go round and round

This is where the coffee came in handy. What are these decomposed matrices? They are the compressed version of what happened. They are telling the story of what the users actually picked/ordered. So is organized by what folks want, not product attributes.

Let’s say for a second that each factor is simply 1 and 0. If each product is in 20 factors, and you can combine these factors factorial(20) times to get 2 followed by 18 zeroes combinations. That’s a large space of possible carousels. We have real numbers, not integers, so this space is even larger.

Hierarchical clustering is a technique to break clusters into sub-clusters. Imagine each product sitting in it’s own cluster, organized by dissimilarity. Then you take the two most similar clusters, join them and compute dissimilarities between them using Lance–Williams dissimilarity update formula. You stop when you have only one cluster, all the products. You could also have done this the opposite way, top-down. Here is what it looks like when it’s all said and done for these products.

The advantage is that we can stop with top 3 clusters, and zoom down to any level we want. But how many clusters is an appropriate starting point, and how do we name these clusters?

Naming is hard

Explainability with ML is hard. With Bayesian, since we are starting attribute first, it comes naturally (see, I like Bayesian). We have our beautiful with all products and 20 categories. Let’s get an intuition for this by cutting at tree into 20 clusters.

I then compare these clusters to the product attributes and notice some trends. For example, cluster 9 has –

Cluster 10 has –

This is a lot but even if we filter to tops, these are different products

Cluster 9 tops

Custer 10 tops

So yes, these can be named via description of what product attributes show up, or via filtering by attribute. I have some ideas on experiments I want to run next week after validation.

Sidenote: AI

In our previous experiment, we had minimized KL divergence between expert tags and inventory. Although this isn’t the metric we care about, but we got 40% top-1 accuracy and 60% top2 (of 8 possible classes).

I got the evaluation set that I had predicted on. We got 41% for top-1 and 64% for top-2. The good news is this is consistent with our validation set although not down to per-class accuracy. But are these results good or bad?

There are two kinds of product attributes. I like to define them as facts (red, gown) and opinions (formality, style persona, reviews). Now of course you can get probability estimates for opinions to move them closer to facts. But imagine if you didn’t need them.

If we can do this well to match opinion tags with 645 styles, it means the space captured via Deep Learning is the right visual space.

What’s better, we can do this while buying new products. Currently the team is using DeepDress to match products to previous ones we had and comparing performance. We can do better if we map these to user clusters and carousels… we can tell them exactly which users will order the product if they bought it right now! This is pretty powerful.

However we have to prioritize. I always insist that the most important thing is to build full data pipeline end-to-end. Model improvements can come later.

So right now, the most important thing is to build the validation pipeline. We will use that to validate the ML baseline and the Bayesian baseline when ready. We will have to build the delivery, serving and measurement pipeline too. Once we are done with all that, we will come back to this and explore this idea.

Live Reco build days 2-3 – Unlimited recommendation models

This is second post in the series started here. The goal of this experiment is to help new data scientists see how things are really built outside textbooks and kaggle. Also, if you want to work on challenging real world problems (not ads), come work with us.

The previous post covered proposals with Engineering because data science can’t stand without their shoulders. There is no mention of the model. This is intentional. Before you build anything, it is important to establish what success looks like. Data science classes have it all backwards, that you are given clean pertinent data and the metric, and you can just apply your favorite model. Real life is messy.

So let’s talk about what is our success metric for Data Science Track.

When an Unlimited customer is ready to swap out for a set of new dresses, she comes to our site and browses. This is a long cycle where she will try a lot of different filters and pathways to narrow down the products she wants. These products are filtered by availability at the time. We are not a traditional e-commerce site and are out of some dresses at any given point. If we don’t have a barcode in her size, we won’t display it that day. This is controlled by a home-grown complicated state machine software called reservation calendar. Think hotel bookings.

We can’t control what will be available the day she comes back. So there are a few metrics that might matter:

- PICKS: Does she pick the dress that was recommended?

- SESSION_TIME: Does it take her less time to get to the dress? Is the visit shorter?

- HEARTS: Did she favorite the dress. So even though she won’t pick it this time, she likes it and could rent it later.

I like PICKS because it is the most honest indicator of whether she was content. However availability skews it – she might have picked that dress if it were available that day.

SESSION_TIME is interesting because while this is a great theory, nothing shows conclusively that spending less time on site reduces churn. If anything, we see the opposite. This is because an engaged user might click around more and actually stay on the site longer. Since I don’t understand all these dynamics, I’m not going to check this now.

HEARTS is a good proxy. However it is possible that she might favorite things because they are pretty but not pick them. This was the case at Barnes & Nobles where I pulled some Facebook graph data and found little correlation with authors people actually bought. However, we have done a lot of analysis where for Unlimited users, this correlates with picks very nicely. So Unlimited users are actually using hearts as their checkout mechanism.

We also have shortlists, but all shortlists are hearts so we can just focus on hearts for now.

OK, so we all agreed that HEARTS is the metric we will tune against. Of course, PICKS needs to be monitored but this is the metric we will chase for now.

Now that we have the metric, let’s talk data.

We have:

- membership information

- picks (orders)

- classic orders

- product views

- hearts

- shortlists

- searches and other clicks

- user profile – size, etc

- reviews

- returns

- Try to buy data

For a new data scientist, this would be the most frustrating part. Each data has it’s own quirks and learnings. It takes time to understand all those. Luckily, we are familiar with these.

Baseline Models

We want a baseline model. And ideally, more than one model so we can compare against this baseline and see where we are.

Current recommendations are running on a home grown Bayesian platform (written in scala). For classic recommendations, they are calculating :

P(s | u) = P(e | u) * P(s | e)

where s = style (product). u = user, e = event.

In other words, it estimates the probability of user liking a style based on user going to an event. We use shortlists, product views and other metadata to estimate these.

Since we have this pipeline already, the path of least resistance would be to do something like

P(s | u) = P(c | u) * P(s | c)

where c is a carousel. And we can basically keep the same math and calculations.

But what are these carousels?

There are global carousels, user carousels based on some products (like product X) and attribute based.

An attribute carousel is something like ‘dresses for a semi-formal wedding’. We have coded these as formalities (subjective but lot of agreement). They could be tops with spring seasonality, etc.

OK, but this poses a problem. The above model is using a Dirichlet to calculate all this and there is an assumption that different carousels are independent.

Is this a problem? We won’t know till we build it. And the path to build this is fast.

What else can we do?

When I joined RTR 4+ years ago, the warehouse was in MySQL and all click logs were in large files on disk. To roll out the first reco engine, I created our current Data Warehouse, Vertica which is a Massively Parallel Processing RDBMS. Think Hadoop but actually made for queries. This allowed me to put the logs in there, join to orders, etc. I could talk about my man crush on Turing aware winner, Michael Stonebraker but this is not the time to geek out about databases.

Importantly, it also allows R extensions to run on each node. So besides bringing the data warehouse to the 21st century, I used that to create recommendations that run where the data is. This is how we did recommendations till two years ago when we switched to the Bayesian model I described above.

I used Matrix Factorization Methods that I have described before. The best one was Implicit where we don’t use ratings but rather implicit assumption that anything picked is the same. This aligns nicely with our problem. So my plan was to try it with this data.

My old production code is long gone but I still have what I used for testing here. It’s written in Rcpp (C++ with R bindings) and performs fairly well. It does not use sparse matrices (commit pending feature request in base library). We have to rewrite this in scala anyway so that might be the time to scale this out (batch gradient descent and other tricks). But we can run it right now and use this algorithm to see if it’s worth the effort.

This bears repeating, Implicit Matrix Factorization or SVD++ is the model you want to baseline against if you are new to this. DO NOT USE cosine distances on your user x product matrices. That won’t scale.

AI

Three years ago, I also started working on AI (like everyone). But mostly because I realized that our product is visual. And we could only go so far with stylist tagged attributes. This led to a few products, which are collectively called DeepDress AI internally. The most outward facing is this Chrome extension that will let you rent a dress on any e-retailer’s page. There are also lesser features like visual search via App, product to product recommendations. The most creative is a tool used by the Buying team to check which products match the ones they are considering, and how did they do in the past?

I obviously want to leverage that research here. However it won’t be the baseline. It will be the next model we try.

Carousels go round and round

For both algorithms, we first need to get more clarity on carousels. Sean built an internal visualizer using R/Shiny and we asked our buyers and fashion teams to rate a product in 8 classes -> minimalist, romantic, glamorous, sexy, edgy, boho, preppy, casual. No explanations were given but that team is highly sophisticated and has a very good view of this taxonomy.

One view is that these merchandising tags along with formality tags (from 1-apparel to 10-ballgowns) would form the first set of carousels.

My contention is that if we use SVD++ or AI, the latent space should be explainable since the product is visual. However there is a risk we won’t be able to find meaningful things within the timeframe.

So we broke this problem down into two sections:

- Sean to verify the validity of these style tags. And collect more by working with other teams.

- I will try to predict these style tags using AI (ideally DeepDress). Time is of the essence. If I can prove this out, Sean does not have to ask the other teams.

- Once Matrix Factorization is done, I will explore to see if I can find meaningful things there

I had started looking to predict these style tags five days before we started the project. But couldn’t finished it. I tried to spend an evening after work looking to see if there is something there.

style personas

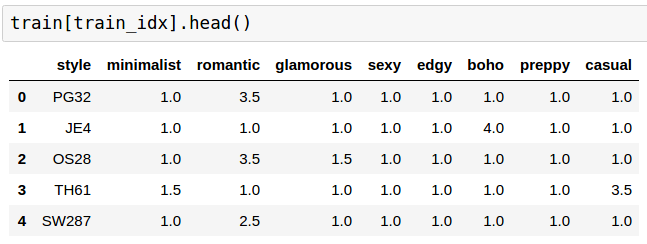

When buyers log into Sean’s sytem, they get a product and have to rate all eight style personas between 1 and 8. Once a style gets 10 ratings, it is not shown again.

So while Sean is embarking on finding out of 10 ratings have agreement, I started to predict them via looking at the dress itself and nothing more.

This is a throwaway model. Even if it works, it just proves that DeepDress captures the essence of these style persona attributes and we can use AI directly. So I have to timebox it.

At this point, there are only 1418 styles that have been completed. I received the medians of these ratings for 60% of the data, 851 styles. This is what the data looks like –

out of which 32 are all 1s.

So I have only 819 examples where we don’t always have a clear dominant class. I further divided that into my own train/validation styles with 80/20 split. At the end I have only 645 styles I am training on.

This would normally be hopeless. But one trick is to take a network trained a larger dataset and perturb the weights by very little. This is called finetuning in literature.

I could have fine-tuned DeepDress but instead I started by fine-tuning Vgg11 to get going quickly.

The model looks like this –

FineTuneModel (

(features): DataParallel (

(module): Sequential (

(0): Conv2d(3, 64, kernel_size=(3, 3), stride=(1, 1), padding=(1, 1))

(1): ReLU (inplace)

(2): MaxPool2d (size=(2, 2), stride=(2, 2), dilation=(1, 1))

(3): Conv2d(64, 128, kernel_size=(3, 3), stride=(1, 1), padding=(1, 1))

(4): ReLU (inplace)

(5): MaxPool2d (size=(2, 2), stride=(2, 2), dilation=(1, 1))

(6): Conv2d(128, 256, kernel_size=(3, 3), stride=(1, 1), padding=(1, 1))

(7): ReLU (inplace)

(8): Conv2d(256, 256, kernel_size=(3, 3), stride=(1, 1), padding=(1, 1))

(9): ReLU (inplace)

(10): MaxPool2d (size=(2, 2), stride=(2, 2), dilation=(1, 1))

(11): Conv2d(256, 512, kernel_size=(3, 3), stride=(1, 1), padding=(1, 1))

(12): ReLU (inplace)

(13): Conv2d(512, 512, kernel_size=(3, 3), stride=(1, 1), padding=(1, 1))

(14): ReLU (inplace)

(15): MaxPool2d (size=(2, 2), stride=(2, 2), dilation=(1, 1))

(16): Conv2d(512, 512, kernel_size=(3, 3), stride=(1, 1), padding=(1, 1))

(17): ReLU (inplace)

(18): Conv2d(512, 512, kernel_size=(3, 3), stride=(1, 1), padding=(1, 1))

(19): ReLU (inplace)

(20): MaxPool2d (size=(2, 2), stride=(2, 2), dilation=(1, 1))

)

)

(fc): Sequential (

(0): Linear (25088 -> 4096)

(1): ReLU (inplace)

(2): Dropout (p = 0.5)

(3): Linear (4096 -> 4096)

(4): ReLU (inplace)

(5): Dropout (p = 0.5)

)

(classifier): Sequential (

(0): Linear (4096 -> 8)

)

)

I decided on minimizing KL-divergence which meant the last layer should do log_softmax(). It also means I normalized the input by subtracting 1 and dividing by the sum of the row to make things add up to 1, a valid probability distribution.

To train this, all rows are frozen except last one for first 100 epochs. It also reduced the learning rate every now and then.

I then went to sleep and the model churn away on my tiny laptop with a small GPU.

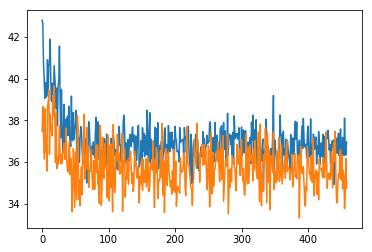

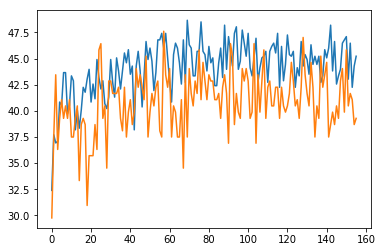

I woke up to these long loss curves

where orange line is train loss and blue is validation loss. They are so jarry because of dropout, random modifications to training images, I’ve tuned them for too long and really, too little data. I could spend more time debugging but won’t for now.

I also calculated accuracy as comparing the highest probable class. If there are two, I took the first one. So if the highest probability was for minimalist, then I was checking to make sure that the highest in predictions is also the same. TOP1 accuracy was then around 40%

(zoomed in TOP1 accuracy)

I also calculated TOP2 accuracy that comes out to be 60%.

I chose the model at an epoch with highest TOP2 accuracy in validation set.

Here, per class TOP1 accuracy in my own validation set comes out to be –

Accuracy of minimalist : 25 % Accuracy of romantic : 75 % Accuracy of glamorous : 31 % Accuracy of sexy : 25 % Accuracy of edgy : 25 % Accuracy of boho : 68 % Accuracy of preppy : 43 % Accuracy of casual : 37 %

Did we overfit? Are these terrible results? I don’t know yet but I am not running a GAN for this.

Here is the code in pytorch, in case anyone has a similar problem: Finetune to minimize KL-divergence.

Wait till tomorrow to know how this works out as well as other experiments.

PS. Featured image via Mahbubur Rahman

PPS. Does the above sound interesting? Come work with us

Live blogging building a production recommendation engine in 30 days

Vanity

We are all guilty of it. Every tech team wants to show off their stack as this big beautiful Ferrari they are proud of. What they often omit is what is glued together by duct tape and 20 other cars they built without engines.

I think this is disparaging to new data scientists. Creating these things is full of false starts and often you end up not where you intended to go, but a good enough direction. They need to see where experts fail, and where they prioritize a must have vs nice to have. Let’s get our hands dirty.

RTR tech is World class. This is going to be the story of how this team will be able to deliver that Ferrari in a month! I hope this gives you insight on how to build things in practice and take away some practical wisdom for that Lamborghini you are going to build.

Backstory

It was a couple of weeks ago that I was sitting in a room with Anushka (GM of Unlimited, our membership program), Vijay (Chief Data Officer, my boss) and Arielle (Director of Product Management, putting it all together). We had a singular goal – how to make product discovery for Unlimited faster. The current recommendations had served us well, but we now need new UX and algos to make this happen. We had learnt from surveys and churn analysis that this is the right thing to work on. But we were short on time from when we start. We had to have a recommendation engine in a month.

Unlimited is your subscription to Fashion. Members pay $139 a month for 3 items at a time. They can hold it for as long as they want. They can return them and get new ones, or buy them. The biggest selling point is our amazing inventory. We have a breadth of designer styles at high price points. So you can dress like a millionaire on a budget.

At high level, we want carousels of products, that are appropriate for that user’s style and fit, a la Netflix, Spotify. We want this to update online (current one is offline) and give recommendations to new users when they start. We want different sorts of carousels – ones made by the algorithms showcasing their styles, vs sorting others by our stylists. And still others saying “because you like X”.

This is naturally impossible in this timeline. However, I did build the first recommendation engine for RTR from the ground up all five years ago. I had also built the current recos for Unlimited when the program was new. We had a lot more existing pipelines and resources I could use. Plus I was getting help this time around, Sean, a bright young analyst who wants to get into Machine Learning.

This is the reality of startups. You can spend a lot of time getting something prioritized on the roadmap, and when it is, it’s a short window. And you can’t miss.

So we aren’t going to miss. And to keep me honest, I’m going to try to write about the process here. Fair warning, I’m not a habitual blogger and doing this after a full day of work, so we will see if this lasts.

What we have:

- Offline recos computed by a scala job

- Pixels (messages) coming back with what the user actually did

- MPP Data warehouse that can process pixels, orders, views, etc

- Serving pre-computed recos via a reco engine that is basically a giant cache. It serves user->products, user->events, event->products, products->products. All models pre-computed offline.

- An AI platform I built to understand images, called DeepDress, powering some products

- Lots of models from my previous research regarding our recommendations

We now have to deliver online recos, and by carousel.

My plan of attack:

- Reuse things we have built before

- Make the end-to-end pipe (data -> algo -> validation -> serving -> data)

- Make sure validation framework is in place, we need to know which metric correlates to outcome we really want to measure (churn).

- Keep it simple, we need a baseline we can improve on. Ideally two algorithms to compare.

- Allow for misses. Things aren’t going to be perfect, account for them up-front.

- Make sure Sean learns something tangible here that gets him excited about doing more things, not overwhelmed.

- Make sure any shortcuts are documented with TODOs and MEHs. We need to know where the duct tape is in context.

Let’s break it down into tracks – engineering, data science, design/product.

The engineering architecture

Before we agree on what to build, we need to agree on what success from the Engineering metrics looks like. So I proposed the following engineering metrics,

- Things will go wrong, we need safety valves:

- Code breaks – Uptime SLA (say 90%), should have fallbacks.

- Latency SLA:

- computation takes longer than say 200ms so we have to return something to the user.

- New recos reflect the actions taken by the user, in say less than 30 minutes. This means that recos should reflect actions taken by users at most 30 minutes ago.

- Flexible: We don’t know what model will work. We will change this often and experiment.

- Scaling: We need to be able to scale horizontally. This pipe should eventually replace our Classic (regular recos) pipe.

- Separation of concerns: What does Data Science do, what does Engineering do

- Language used: Engineering uses JAVA for all backend services. I have used C++ (wrapped in R) in the past, JAVA for another solver for fulfillment, scala for refactor of personalization with Anthony (who is now at Google).

Our simple proposal based on all this at the time is to create a scala library that we use to create the model. And the same library can used by the online portion at Engineering writes to load and predict from the model. This is the path of least resistance because JVM allows them to call it seamlessly, and we already have offline recommendations being computed by a Bayesian model written in scala.

The big thing here is that the JAVA portion (owned by Engineering) will have multiple fallbacks. For every type of recommendation, it can go to a set of carousels and products it can deliver. Strictly speaking, Data science ML library is research and the code to serve them is Engineering. If the ML library throws an exception, the engineering portion should know what to do about it (go to previous version of model, etc).

The other is scaling, each online serving shard only needs to know about a subset of users. We will use LSH tricks for this.

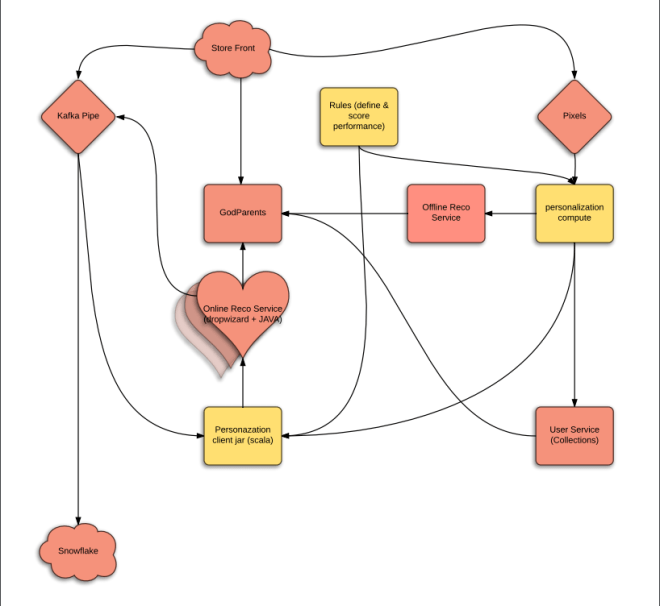

Here is the cartoon version of what we jointly proposed:

The yellow parts are new as well as the heart.

Being a software architect in early 00s makes me believe that I can still do it. However, I’m frequently wrong. Luckily John (Director of Engineering) and Jade (Director of Platoform services) took it over and rescued the drowning baby. They thought of all the edge cases and we made a lot of decisions on what we can and cannot do for MVP. Jay (Director of ETL) took over the pipeline cartoon drawing here and came up with a robust proposal that actually works with our new data warehouse – Snowflake.

The pink parts are owned by Engineering and yellow by Data Science.

OK, we have very rough edges for engineering. John is spearheading this. He broke it down with Engineering Leads (Rod and Devin) and the deeply talented engineering team (Christine, August, Denitza, Jon and Kaixi). He has all the way from user stories down to actual API requirements that MLLib needs to respond to. We also have an open question on language for the MLLib, so we are trying to get consensus.

But this seems possible to do in three sprints given the talent we have. Each sprint is 2 weeks, which is 10 working days each. So yeah, 30 days*.

This is parallel to the algorithms and design tracks. We will talk about that tomorrow.

Off to the races…

P.S got delayed posting this (today is Thursday, not Monday), but will try to keep the timeline.

PPS. Does the above sound interesting? Come work with us

<featured image via here>

Dreaming up new dresses via AI and game theory

Level: Beginner, circa 2014

Or I can haz fashion.

Here are some pretty pictures to motivate you

These are all ‘dreamt’ by a neural net. OK, now for the old bait and switch. Let’s talk Deep Learning for a second.

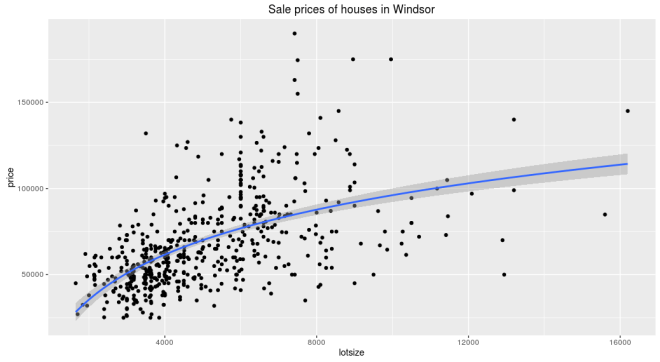

For the uninitiated, traditional machine learning works something like this. Say you are trying to predict housing prices using square footage. You have relevant data with those fields. So you plot the two and see if there appears to be a relationship.

Looks like there is. Usually, you start with a simple algorithm to learn that relationship. Let’s say we used linear for starters, which gets us –

price ~ 6.6 * lotsize + 34,136

Then you look at the errors, and you aren’t satisfied. Maybe this isn’t a straight line after all. Often the next thing to try is to transform the input parameters to make them look linear. So a typical transform in the above case would be natural log. Now the relationship looks like this

and equation

price ~ 37,660 * log(lotsize) - 250,728

And you are rewarded with better results. These sort of transforms are the bread and butter of traditional machine learning. But of course we prefer a fancier term, feature engineering.

But what are you really doing? You are transforming the input space to make the simple line fit. You still want to fit a line, but are mangling the input plane to make it go through that line. It’s like holding your breath to shimmy into a pair of jeans you have owned for longer than you should.

What if you could let the model transform the input all it needs, and build on top of the last transform one step at a time, to put the data in the right shape for your classifier? That’s exactly what deep learning does for you. And at the end, the last layer is a simple linear classifier.

This isn’t exactly a new concept, Bayesians already do this. But they don’t have a fast enough algorithm yet and the models are a bit too custom – making it hard to generalize to a new problem.

We are going to talk about dresses, so the right data format happens to be photos. To a computer, that is a matrix of numbers of height x width x 3 channels (Red, Green, Blue).

Sidenote: The above representation is not perfect. It is important to note that photo format has limitations. In real life, you don’t have borders (padding), you can move your eyes and see further. Borders are a limitation of the medium. Real vision is a fluid and complex thing (mind fills in details, nose is invisible, etc). Photos are just a good approximation of that.

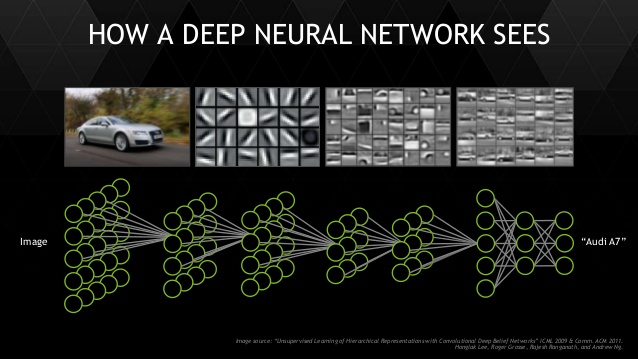

Convolution transforms are designed specifically to learn from this format. It’s job is to transform the input space spatially. So lower layers do versions of edge detection, blurring, etc. And higher layers begin to understand that the combination of which edges means a collar or a sleeve. Finally, linear classifier on top as before to figure out which dress it is. As before, the model learns which convolutions to do in order to achieve the final result. It is not taught edge detection specifically but it will decide to detect a particular edge if it makes it easy for the linear classifier.

Deep learning is responsible for some impressive results. However, those impressive results require lots of data. If you aren’t so lucky, there still are a few options.

One option is transfer learning. The basic idea is that you train the network to learn to distinguish between objects on a large dataset. Then freeze the early layers and train just the last few layers very slowly on your data for it to understand how the same corners it learnt by distinguishing cats and dogs. can be used to piece together a dress.

In my experience, this tends to overfit. In other words, it doesn’t work as well for new (unseen) data. And we don’t get those advertised 90+% accuracy.

So what else can we do?

Here is a crazy idea (thanks Ian Goodfellow, 2014). Why don’t we generate our own data?

There are other data augmentation techniques (adding noise to existing input, Bayesian techniques and others) but I was looking for an excuse to generate sharp pictures of dresses anyway. So that’s what we will do.

Our net that distinguishes between classes is called a discriminator (missed opportunity to call it connoisseur). For now, we will assume all it does is say whether or not what it sees is a dress.

The idea is to invert this discriminator to generate from noise. This is called a generator. This involves inverting the convolution to a deconv layer. The loss is also negative of the Discriminator loss.

We pitch the two nets against each other but with an odd setup. In the first half of the game, we sample real data and the discriminator tries to say that this is a dress. In the second half, the generator takes in random noise and comes up with a new dress. We then sample and feed that to our discriminator that tries to say that this is not a real dress. We then back propagate the errors through the whole thing.

Over time the discriminator tries to create fakes to fool the generator. And generator tries to guard against this treachery. This goes on till they reach an equilibrium. At this point the discriminator can no longer tell real from fake dresses (50/50). Yes guys, this was the time for game theory.

We now have two nets – a much better discriminator than before because it trained on a lot more data. And a generator that can generate decent fakery.

But you ask, I thought this was ‘sane’ alytics. Where is the practical stuff!

Well, the discriminator has been fed a steady diet of fake dresses and is better at telling real from fake than when it started. It overfits less because it has trained on more data. And sure, we get the generator for free. The images in this article are from the baseline (Alexnetish) generator but theoretically using something better like Resnet should work even better.

Here are some original sample pictures that we had for input

Here are some results from the generator after training.

And let’s make the distinction from adding noise to data. This is generating data from noise. See this transition to understand how it evolves over training iterations.

The discriminator learns to distinguish between this being a dress vs any fake samples. The generator plays the game and is still generating not very dress like samples at 500 iterations

And after 130,000 iterations, it can generate something like this

Here is a snippet of how it learns

While not perfect, this is impressive from two years ago when this was first introduced.

But wait, there is more. Folks have been able to generate new bedrooms, improve resolution of a photo (CSI Enhance!), make folks with RBF smile, predict what happens in the next frame of the video (compress) and generated colorful birds from text.

We don’t yet know everything GANs can do. But it is already proving to be a useful tool.

Want to generate on your own data? See DCGAN code from Facebook here and (more efficient!) WassersteinGAN here.

Want to learn more? Here is a deeper dive on different kinds of GANs.

This is a rapidly evolving field, so new papers come out all the time. We aren’t too far from dreaming up different dresses for everyone’s personal style and fit, at scale.

Human in A.I. loop

A.I is out to get us. It will replace us all.. or maybe, it’s just another tool that we will get used to like calculators or iPhones.

If you are reading this post, chances are you are familiar with Artificial Intelligence, Deep Learning, Neural nets. I am not going to be pedantic and use them interchangeably.

If you don’t care for any of that, feel free to read this article as “Human in Machine Learning loop”. Or how to debug beyond metrics (smell a pattern in this blog?).

Let’s start with a practical example of something I built at Rent The Runway. RTR rents out high end designer dresses for a mass market price. We have a lot of folks who love us. And they are not shy about tagging us on their Instagram posts.

Wouldn’t it be great if we could show those Instagram photos on our product pages and help our customers find fashion inspiration through these high quality shots?

We already have photo reviews that our customers post on our site showing us how they wore it. It is a highly used feature for visitors. But customers have to submit to us directly for that to work.

My mind was set. It had to be done.

But how? While it is true that they tag #renttherunway or #myRTR, they don’t tag the exact dress name.

Obviously I brought a tank to a knife fight and built a convolutional neural net. This A.I that would look at these natural images and classify them as one of the thousands of dresses that we have currently on site. I named it DeepDress, but probably should have called it Dress2Vec… too late now. I used Torch to train and Benjamin’s waffle package to create an internal API that I can hit from any language. Since I have little patience, I used NVIDIA GPUs to speed up the training and tests.

I got all 30k Instagram posts at the time and I stored the metadata in Mongo (I know, I know but it’s great for unstructured).

Here is the code for that –

This file contains hidden or bidirectional Unicode text that may be interpreted or compiled differently than what appears below. To review, open the file in an editor that reveals hidden Unicode characters.

Learn more about bidirectional Unicode characters

| import urllib.request | |

| import json | |

| from pymongo import MongoClient | |

| import time | |

| def fetchAndStash(url, client): | |

| try: | |

| response = urllib.request.urlopen(url + '&count=100') | |

| f = response.read() | |

| payload = f.decode('utf-8') | |

| j = json.loads(payload) | |

| if j['meta']['code'] == 200 : # Request worked | |

| for i in j['data']: # Loop through Instagram posts and save them | |

| try: | |

| # Hardcoded Database/Collection names.. change this | |

| result = client.DeepDress.InstagramV4.insert({'_id' : i['link'], 'payload' : i, 'image' : i['images']['low_resolution']['url']}) | |

| except: | |

| print("bad batch url: " + url + '; tried to insert ' + i) | |

| with open('error', 'a') as of: | |

| of.write(f.decode('utf-8')) | |

| time.sleep(1) # Be nice | |

| fetchAndStash(j['pagination']['next_url'], client) # Follow the white rabbit | |

| else : | |

| print(url) | |

| except: | |

| print("Failed url ", url) | |

| def main(): | |

| client = MongoClient() | |

| url = 'https://api.instagram.com/v1/tags/renttherunway/media/recent/?client_id=your_client_id_here' | |

| fetchAndStash(url, client) # could hit stack overflow.. but unlikely | |

| if __name__ == "__main__": | |

| main() |

Then I looped through them and called my API to identify the dress and saved that.

This file contains hidden or bidirectional Unicode text that may be interpreted or compiled differently than what appears below. To review, open the file in an editor that reveals hidden Unicode characters.

Learn more about bidirectional Unicode characters

| import urllib.request | |

| import json | |

| from pymongo import MongoClient | |

| import time | |

| from multiprocessing import Pool | |

| DEEP_DRESS_WGET = 'http://localhost/wget/?url=' | |

| DEEP_DRESS_PREDICT = 'http://localhost/predict/' | |

| def wget_deep_dress(url): | |

| serviceurl = DEEP_DRESS_WGET + url | |

| response = urllib.request.urlopen(serviceurl) | |

| f = response.read() | |

| j = json.loads(f.decode('utf-8')) | |

| return(j['file_id']) | |

| def predict_deep_dress(file_id, top_n): | |

| serviceurl = DEEP_DRESS_PREDICT + '?file_id=' + file_id + '&top_n=' + top_n | |

| response = urllib.request.urlopen(serviceurl) | |

| f = response.read() | |

| j = json.loads(f.decode('utf-8')) | |

| return(j) | |

| client = MongoClient() | |

| db = client.DeepDress | |

| instagram = db.InstagramV4 | |

| matches = db.MatchesV4 | |

| # already tagged | |

| ids = set([m['_id'] for m in matches.find()]) | |

| def match_and_save(i): | |

| try: | |

| if (i['_id'] not in ids): | |

| file_id = wget_deep_dress(i['image']) | |

| preds = predict_deep_dress(file_id, '3') | |

| result = matches.insert({'_id' : i['_id'], 'prediction' : preds}) | |

| time.sleep(1) # Be nice | |

| return(1) | |

| except: | |

| return(0) | |

| pool = Pool(processes=5) # Don't make this too high – rate limits | |

| totals = pool.map(match_and_save, instagram.find()) | |

| print(sum(totals), len(totals)) |

Mission accomplished and moving on.

Well my friends, if that were the case, I wouldn’t have written this post. So here is how a production system is really built.

One problem I knew ahead of time is that our inventory changes over time as we retire older styles and acquire new ones. DeepDress did not know of some very new dresses and none of the old ones. Old ones aren’t an issue since we wouldn’t want to display them anyway but there is a cold start problem that I hadn’t solved at the time.

Another issue is that I had trained the algorithm only on our dresses. While that is our bread and butter, we also rent bags, earrings, necklaces, bracelets, activewear, etc. I always start simple for v1. This means there were bound to be things classified incorrectly as the convnet sweats bullets trying to figure out which dress that Diane Von Furstenberg minaudiere looks like. We could use a lower bound on the probability of most likely class, but what should that threshold be?

Besides the above red flags, even if the identification were 100% accurate (ha), it would make sense to have someone in RTR verify that the image is in fact, fit for display on our site and consistent with our branding.

What we need to build is a gamified quick truther thingy that all our 200 employees in main office can log in during their lunch break and rate a few items. It better be interesting and fast because they have important things to do. It wouldn’t hurt to get verification of the same image from a few different folks so we build our confidence. Then there are nice to haves like responsive, reactive, and other fancy words that mean fun to use.

I could have built this in ruby or react or something that pleases my web developer friends. But I am a data scientist who is very familiar with R, so I built another shiny little thing in an hour. I am in good company. My friend Rajiv also loves understanding his A.I. creations in R.

Rough outline on what we want –

- Start with a random seed for each session

- Retrieve Instagram Images from that seed backwards

- User has to choose one of N options

- Upon choice, store the result back in Mongo

- Automatically move on to the next one (shiny is responsive)

- Every day, a job would restart the server, freezing what was done and starting on the next batch, moving back in time.

First we set up the global.R to get the relevant Instagram posts we will verify –

This file contains hidden or bidirectional Unicode text that may be interpreted or compiled differently than what appears below. To review, open the file in an editor that reveals hidden Unicode characters.

Learn more about bidirectional Unicode characters

| library(mongolite) | |

| # Connections to mongo | |

| instagram <- mongo(collection = "InstagramV4", db = "DeepDress", url = "mongodb://localhost", verbose = FALSE) | |

| matches <- mongo(collection = "MatchesV4", db = "DeepDress", url = "mongodb://localhost", verbose = FALSE) | |

| corrections <- mongo(collection = "CorrectionsV4", db = "DeepDress", url = "mongodb://localhost", verbose = FALSE) | |

| # Get Instagram data we saved earlier | |

| ids.df <- instagram$find(fields = '{"_id" : 1, "payload.created_time" : 1}') | |

| ids.df.simple <- data.frame(id = ids.df$`_id`, | |

| created_time = ids.df$payload$created_time, | |

| stringsAsFactors = FALSE) | |

| # Reorder by newest | |

| ids.df.simple <- ids.df.simple[order(-as.numeric(ids.df.simple$created_time)), ] | |

| # What has already been corrected by users | |

| ids.done <- corrections$find(fields = '{"id" : 1}') # What has already been corrected | |

| # What's left | |

| ids.df.todo <- setdiff(ids.df.simple$id, ids.done$id) |

Then we create ui.R that my colleagues will see –

This file contains hidden or bidirectional Unicode text that may be interpreted or compiled differently than what appears below. To review, open the file in an editor that reveals hidden Unicode characters.

Learn more about bidirectional Unicode characters

| library(shiny) | |

| shinyUI(fluidPage( | |

| # Application title | |

| titlePanel("Verify Auto-tagged dresses from Instagram"), | |

| # Sidebar with a slider input for number of bins | |

| sidebarLayout( | |

| sidebarPanel( | |

| textInput("email", "Your email", placeholder = "So that we can attribute the correction to you"), | |

| htmlOutput("instagram"), | |

| radioButtons("yesorno", "Accept tag?", | |

| c("Not a dress", "First", "Second", "Third", "None"), selected = "None"), | |

| actionButton("submit", "Submit"), | |

| helpText("Click the photo to see the original Instagram"), | |

| helpText("DeepDress AI might not know about some newer dresses. Esp dresses with <= 10 photo reviews"), | |

| helpText("The AI was written to match ANY PHOTO to our dresses. It does not know if what it is seeing is not a dress."), | |

| helpText("FAQ: Use 'Not a dress' if it is a Handbag, jacket, car or flower.. anything that's not a dress.") | |

| ), | |

| # Show a plot of the generated distribution | |

| mainPanel( | |

| htmlOutput("deepDress"), | |

| hr(), | |

| h4("Match probability"), | |

| textOutput("deepDressProb") | |

| ) | |

| ) | |

| )) |

Finally we need to hook up some logic –

This file contains hidden or bidirectional Unicode text that may be interpreted or compiled differently than what appears below. To review, open the file in an editor that reveals hidden Unicode characters.

Learn more about bidirectional Unicode characters

| shinyServer(function(input, output, session) { | |

| # Session level | |

| idx <- round(runif(1, 1, 2500)) # random place to start | |

| state <- reactive({ | |

| if(input$submit > 0) { # Not on first page load | |

| isolate({ # Don't get reactive on me now | |

| answer <- input$yesorno | |

| m <- matches$find(query = paste0('{"_id": "', ids.df.todo[idx], '"}'), fields = '{}' ,limit = 1, pagesize=1) | |

| answer.clean <- ifelse(answer == "First", | |

| m$prediction$styleNames[[1]]$style[1], | |

| ifelse(answer == "Second", | |

| m$prediction$styleNames[[1]]$style[2], | |

| ifelse(answer == "Third", | |

| m$prediction$styleNames[[1]]$style[3], | |

| answer))) | |

| datum <- data.frame(email = input$email, | |

| id = ids.df.todo[idx], | |

| answer = answer.clean, | |

| ts = Sys.time() | |

| ) | |

| corrections$insert(datum) | |

| }) | |

| } | |

| idx <<- idx + 1 # Keep on moving | |

| }) | |

| output$instagram <- renderPrint({ | |

| state() | |

| i <- instagram$find(query = paste0('{"_id": "', ids.df.todo[idx], '"}'), fields = '{}' ,limit = 1, pagesize=1) | |

| cat(paste0("<a href='", i$`_id`,"' target='_blank'>", | |

| "<img src='", i$image, "' />", | |

| "</a>")) | |

| }) | |

| getFirst <- reactive({ | |

| state() | |

| m <- matches$find(query = paste0('{"_id": "', ids.df.todo[idx], '"}'), fields = '{}' ,limit = 1, pagesize=1) | |

| }) | |

| output$deepDress <- renderPrint({ | |

| m <- getFirst() | |

| cat(paste0("<img src='", m$prediction$styleNames[[1]]$urls$imageURL, "' />")) | |

| }) | |

| output$deepDressProb <- renderText({ | |

| m <- getFirst() | |

| paste(round(m$prediction$styleNames[[1]]$probability), '%') | |

| }) | |

| }) |

And shiny does the rest. Here is what this looks like in practice –

This was so successful that in the two weeks the POC was up, we had 3,281 verifications. Some colleagues (thanks Sam/Sandy) did as many as 350+ verifications over that time. It should be pointed out that besides an announcement email, there was no other push to do this.

We found that there were a significant number of posts that were not even dresses. I guess our fashionistas really love us. This is not a problem I knew about going into building this and was certainly not expecting high probability scores for the suggested class in some cases. It helped me fix it by adding a class for “not a dress” with actual training data (and noise).

Most importantly, we answered important questions like what this cute puppy wore.

And if that isn’t the most satisfying result, I don’t know what is.

We have some amazing employees (hi Sam/Liz/Amanda) who have can remember single dress on site. For mere mortals, matching a photo to something we have is nearly impossible.

DeepDress A.I toiled through all 30k photos and narrowing each down to 3 possible choices from our thousands. But it is humans who really save the day. As a result we have a golden database of Instagram photos mapped to exact product that took advantage of both their strengths. Look at that – humans and A.I can play together.

Hopefully this example demonstrates why it is useful to use your resources (company employees) to check your systems beyond the metrics before releasing things in the wild. I end up using shiny a lot for these sort of internal demos because I slice and dice the results in R. But do them in whatever you are comfortable in and aggressively re-evaluate those choices should they reach production. For example, we will rewrite the truther in Ruby now that it will be production to comply with our other standards. For demos, I have no emotional attachment to any language (close your ears C++).

I’m sure you guessed that could not have been the only reason I built DeepDress and you would be right. But today’s not a day to talk about that.

Matrix factorization

Or fancy words that mean very simple things.

At the heart of most data mining, we are trying to represent complex things in a simple way. The simpler you can explain the phenomenon, the better you understand. It’s a little zen – compression is the same as understanding.

Warning: Some math ahead.. but stick with it, it’s worth it.

When faced with a matrix of very large number of users and items, we look to some classical ways to explain it. One favorite technique is Singular Value Decomposition, affectionately nicknamed SVD. This says that we can explain any matrix in the form

Here

is of size num_users and num_products

is of size num_users and num_users

is a rectangular diagonal matrix of size num_users and num_products

is of size num_products and num_products

This is cool because the numbers in the diagonal are decreasing values of variance (roughly speaking). So the first number captures the most variance in

, the second, less so, and so on, till all the numbers put together capture all the variance of

.

You see where this is going. If we are comfortable with explaining only 10% of the variance, we can do so by only taking some of these values. We can then compress .

The other nice thing about all this is eigenvectors (which those roughly represent) are orthogonal. In other words, they are perpendicular to each other and there aren’t any mixed effects. If you don’t understand this paragraph, don’t worry. Keep on.

Consider that above can be rewritten as

or –

If is of size num_users and num_categories and

is of size num_products and num_categories, then we have a decent model that approximates

into

.

is now called a low rank approximation of

, or truncated SVD.

It is important to understand what these matrices represent. is the representation of users in some low dimension space (say romance, action). And

is the representation of products in the very same low dimension space. However, we don’t know exactly what these factors mean. They could be romance/action or they could NYC/Dallas. This is also why this method is sometimes called Latent Factor Matrix Factorization.. wow, quite a mouthful.

In my chapter in the book Data Mining Applications with R, I go over different themes of matrix factorization models (and other animals as well). But for now, I am only going to cover the basic one that works very well in practice. And yes, won the Netflix prize.

There is one problem with our formulation – SVD is only defined for dense matrices. And our matrix is usually sparse.. very sparse. Netflix’s challenge matrix was 1% dense, or 99% sparse. In my job at Rent the Runway, it is only 2% dense. So what will happen to our beautiful formula?

Machine learning is sort of a bastard science. We steal from beautiful formulations, complex biology, probability, Hoefding’s inequality, and derive rules of thumb from it. Or as an artist would say – get inspiration.

So here is what we are going to do. We are going to ignore all the null values when we solve this model. Our cost function now becomes

Here is the difference between observed data and our prediction.

is simply a matrix with 1 where we have a value and 0 where we do not. Multiplying these two we are only considering the cost when we observe a value. We are using L2 regularization of magnitude

. We are going to divide by 2 to make all other math easier. The cost is relative so it doesn’t matter.

Using this our gradients become –

If we were wanted to minimize the cost function, we can move in the direction opposite to the gradient at each step, getting new estimates for and

each time.

This looks easy enough. One last thing. We now have what we want to minimize, but how do we do it? R provides many optimization tools. There is a whole CRAN page on it. For our purpose we will use out of the box optim() function. This allows us to access a fast optimization method L-BFGS-B. It’s not only fast, but also doesn’t take too memory intensive which is desirable in our case.

We need to give it the cost function and the gradient that we have above. It also expects one gradient function, so we need to unroll it out to do both our gradients.

This file contains hidden or bidirectional Unicode text that may be interpreted or compiled differently than what appears below. To review, open the file in an editor that reveals hidden Unicode characters.

Learn more about bidirectional Unicode characters

| unroll_Vecs <- function (params, Y, R, num_users, num_movies, num_features) { | |

| # Unrolls vector into X and Theta | |

| # Also calculates difference between preduction and actual | |

| endIdx <- num_movies * num_features | |

| X <- matrix(params[1:endIdx], nrow = num_movies, ncol = num_features) | |

| Theta <- matrix(params[(endIdx + 1): (endIdx + (num_users * num_features))], | |

| nrow = num_users, ncol = num_features) | |

| Y_dash <- (((X %*% t(Theta)) – Y) * R) # Prediction error | |

| return(list(X = X, Theta = Theta, Y_dash = Y_dash)) | |

| } | |

| J_cost <- function(params, Y, R, num_users, num_movies, num_features, lambda, alpha) { | |

| # Calculates the cost | |

| unrolled <- unroll_Vecs(params, Y, R, num_users, num_movies, num_features) | |

| X <- unrolled$X | |

| Theta <- unrolled$Theta | |

| Y_dash <- unrolled$Y_dash | |

| J <- .5 * sum( Y_dash ^2) + lambda/2 * sum(Theta^2) + lambda/2 * sum(X^2) | |

| return (J) | |

| } | |

| grr <- function(params, Y, R, num_users, num_movies, num_features, lambda, alpha) { | |

| # Calculates the gradient step | |

| # Here lambda is the regularization parameter | |

| # Alpha is the step size | |

| unrolled <- unroll_Vecs(params, Y, R, num_users, num_movies, num_features) | |

| X <- unrolled$X | |

| Theta <- unrolled$Theta | |

| Y_dash <- unrolled$Y_dash | |

| X_grad <- (( Y_dash %*% Theta) + lambda * X ) | |

| Theta_grad <- (( t(Y_dash) %*% X) + lambda * Theta ) | |

| grad = c(X_grad, Theta_grad) | |

| return(grad) | |

| } | |

| # Now that everything is set up, call optim | |

| print( | |

| res <- optim(par = c(runif(num_users * num_features), runif(num_movies * num_features)), # Random starting parameters | |

| fn = J_cost, gr = grr, | |

| Y=Y, R=R, | |

| num_users=num_users, num_movies=num_movies,num_features=num_features, | |

| lambda=lambda, alpha = alpha, | |

| method = "L-BFGS-B", control=list(maxit=maxit, trace=1)) | |

| ) |

This is great, we can iterate a few times to approximate users and items into some small number of categories, then predict using that.

I have coded this into another package recommenderlabrats.

Let’s see how this does in practice against what we already have. I am going to use the same scheme as last post to evaluate these predictions against some general ones. I am not using Item Based Collaborative Filtering because it is very slow

This file contains hidden or bidirectional Unicode text that may be interpreted or compiled differently than what appears below. To review, open the file in an editor that reveals hidden Unicode characters.

Learn more about bidirectional Unicode characters

| require(recommenderlab) # Install this if you don't have it already | |

| require(devtools) # Install this if you don't have this already | |

| # Get additional recommendation algorithms | |

| install_github("sanealytics", "recommenderlabrats") | |

| data(MovieLense) # Get data | |

| # Divvy it up | |

| scheme <- evaluationScheme(MovieLense, method = "split", train = .9, | |

| k = 1, given = 10, goodRating = 4) | |

| scheme | |

| # register recommender | |

| recommenderRegistry$set_entry( | |

| method="RSVD", dataType = "realRatingMatrix", fun=REAL_RSVD, | |

| description="Recommender based on Low Rank Matrix Factorization (real data).") | |

| # Some algorithms to test against | |

| algorithms <- list( | |

| "random items" = list(name="RANDOM", param=list(normalize = "Z-score")), | |

| "popular items" = list(name="POPULAR", param=list(normalize = "Z-score")), | |

| "user-based CF" = list(name="UBCF", param=list(normalize = "Z-score", | |

| method="Cosine", | |

| nn=50, minRating=3)), | |

| "Matrix Factorization" = list(name="RSVD", param=list(categories = 10, | |

| lambda = 10, | |

| maxit = 100)) | |

| ) | |

| # run algorithms, predict next n movies | |

| results <- evaluate(scheme, algorithms, n=c(1, 3, 5, 10, 15, 20)) | |

| # Draw ROC curve | |

| plot(results, annotate = 1:4, legend="topleft") | |

| # See precision / recall | |

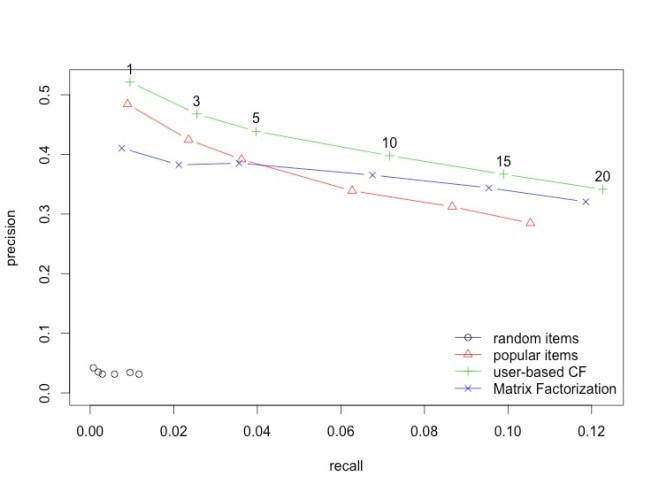

| plot(results, "prec/rec", annotate=3) |

It does pretty well. It does better than POPULAR and is equivalent to UBCF. So why use this over UBCF or the other way round?

This is where things get interesting. This algorithm can be sped up quite a lot and more importantly, parallelised. It uses way less memory than UBCF and is more scalable.

Also, if you have already calculated , i.e. your items in some lower dimensional space, you might get away with just putting the users in that space. Now things become really fast because all you have to do is keep

fixed and figure out

.

I have gone ahead and implemented a version where we just calculate , I leave it to you as an exercise to modify the code above to test this out as well. The algorithm is called RSVD_SPLIT. Also feel free to try other values of categories, lambda and maxit and see how things change.

On the other hand, the latent categories are very hard to explain. For UBCF you can say this user is similar to these other users. For IBCF, one can say this item that the user picked is similar to these other items. But that not the case for this particular flavor of matrix factorization. We will re-evaluate these limitations later.

The hardest part for a data scientist is to disassociate themselves from their dear models and watch them objectively in the wild. Our simulations and metrics are always imperfect but necessary to optimize. You might see your favorite model crash and burn. And a lot of times simple linear regression will be king. The job is to objectively measure them, tune them and see which one performs better in your scenario.

Good luck.

Testing recommender systems in R

Recommender systems are pervasive. You have encountered them while buying a book on barnesandnoble, renting a movie on Netflix, listening to music on Pandora, to finding the bar visit (FourSquare). Saar for Revolution Analytics, had demonstrated how to get started with some techniques for R here.

We will build some using Michael Hahsler’s excellent package – recommenderlab. But to build something we have to learn to recognize when it is good. For this reason we will talk about some metrics quickly –

– RMSE (Root Mean Squared Error) : Here we measure far were real ratings from the ones we predicted. Mathematically, we can write it out as

where is the set of all user-item pairings

for which we have a predicted rating

and a known rating

which was not used to learn the recommendation model.

Here at sane.a.lytics, I will talk about when an analysis makes sense and when it doesn’t. RMSE is a great metric if you are measuring how good your predicted ratings are. But if you want to know how many people clicked on your recommendation, I have a different metric for you.

– Precision/Recall/f-value/AUC: Precision tells us how good the predictions are. In other words, how many were a hit.

Recall tells us how many of the hits were accounted for, or the coverage of the desirable outcome.

Precision and recall usually have an inverse relationship. This becomes an even bigger issue for rare issue phenomenon like recommendations. To tackle this problem, we will use f-value. This is nothing but the harmonic mean of precision and recall.

Another popular measure is AUC. This is roughly analogous. We will go ahead and use this for now for our comparisons of recommendation effectiveness.

– ARHR (Hit Rate): Karypis likes this metric.

where is the position of the item in a ranked list.

OK, on to the fun stuff.

They are a few different ways to build a recommender system

Collaborative Filtering : If my friend Jimmy tells me that he liked the movie “Drive”, I might like it too since we have similar tastes. However if Paula tells me she liked “The Notebook”, I might avoid it. This is called UBCF (User-based collaborative filtering). Another way to think about it is that this is soft-clustering. We find Users with similar tastes (neighbourhood) and use their preferences to build yours.

Another flavour of this is IBCF (Item Based Collaborative Filtering). If I watched “Darjeeling Limited”, I might be inclined to watch “The Royal Tannenbaums” but not necessarily “Die Hard”. This is because the first two are more similar in the users who have watched/rated them. This is a rather simple to compute as all we need is the covariance between products to find out what this might be.

Let’s compare both approaches on some real data (thanks R)

This file contains hidden or bidirectional Unicode text that may be interpreted or compiled differently than what appears below. To review, open the file in an editor that reveals hidden Unicode characters.

Learn more about bidirectional Unicode characters

| # Load required library | |

| library(recommenderlab) # package being evaluated | |

| library(ggplot2) # For plots | |

| # Load the data we are going to work with | |

| data(MovieLense) | |

| MovieLense | |

| # 943 x 1664 rating matrix of class ‘realRatingMatrix’ with 99392 ratings. | |

| # Visualizing a sample of this | |

| image(sample(MovieLense, 500), main = "Raw ratings") | |

This file contains hidden or bidirectional Unicode text that may be interpreted or compiled differently than what appears below. To review, open the file in an editor that reveals hidden Unicode characters.

Learn more about bidirectional Unicode characters

| # Visualizing ratings | |

| qplot(getRatings(MovieLense), binwidth = 1, | |

| main = "Histogram of ratings", xlab = "Rating") | |

| summary(getRatings(MovieLense)) # Skewed to the right | |

| # Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max. | |

| # 1.00 3.00 4.00 3.53 4.00 5.00 |

This file contains hidden or bidirectional Unicode text that may be interpreted or compiled differently than what appears below. To review, open the file in an editor that reveals hidden Unicode characters.

Learn more about bidirectional Unicode characters

| # How about after normalization? | |

| qplot(getRatings(normalize(MovieLense, method = "Z-score")), | |

| main = "Histogram of normalized ratings", xlab = "Rating") | |

| summary(getRatings(normalize(MovieLense, method = "Z-score"))) # seems better | |

| # Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max. | |

| # -4.8520 -0.6466 0.1084 0.0000 0.7506 4.1280 |

This file contains hidden or bidirectional Unicode text that may be interpreted or compiled differently than what appears below. To review, open the file in an editor that reveals hidden Unicode characters.

Learn more about bidirectional Unicode characters

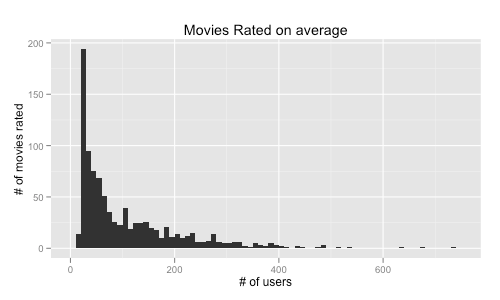

| # How many movies did people rate on average | |

| qplot(rowCounts(MovieLense), binwidth = 10, | |

| main = "Movies Rated on average", | |

| xlab = "# of users", | |

| ylab = "# of movies rated") | |

| # Seems people get tired of rating movies at a logarithmic pace. But most rate some. |

This file contains hidden or bidirectional Unicode text that may be interpreted or compiled differently than what appears below. To review, open the file in an editor that reveals hidden Unicode characters.

Learn more about bidirectional Unicode characters

| # What is the mean rating of each movie | |

| qplot(colMeans(MovieLense), binwidth = .1, | |

| main = "Mean rating of Movies", | |

| xlab = "Rating", | |

| ylab = "# of movies") | |

| # The big spike on 1 suggests that this could also be intepreted as binary | |

| # In other words, some people don't want to see certain movies at all. | |

| # Same on 5 and on 3. | |

| # We will give it the binary treatment later |

This file contains hidden or bidirectional Unicode text that may be interpreted or compiled differently than what appears below. To review, open the file in an editor that reveals hidden Unicode characters.

Learn more about bidirectional Unicode characters

| recommenderRegistry$get_entries(dataType = "realRatingMatrix") | |

| # We have a few options | |

| # Let's check some algorithms against each other | |

| scheme <- evaluationScheme(MovieLense, method = "split", train = .9, | |

| k = 1, given = 10, goodRating = 4) | |

| scheme | |

| algorithms <- list( | |

| "random items" = list(name="RANDOM", param=list(normalize = "Z-score")), | |

| "popular items" = list(name="POPULAR", param=list(normalize = "Z-score")), | |

| "user-based CF" = list(name="UBCF", param=list(normalize = "Z-score", | |

| method="Cosine", | |

| nn=50, minRating=3)), | |

| "item-based CF" = list(name="IBCF2", param=list(normalize = "Z-score" | |

| )) | |

| ) | |

| # run algorithms, predict next n movies | |

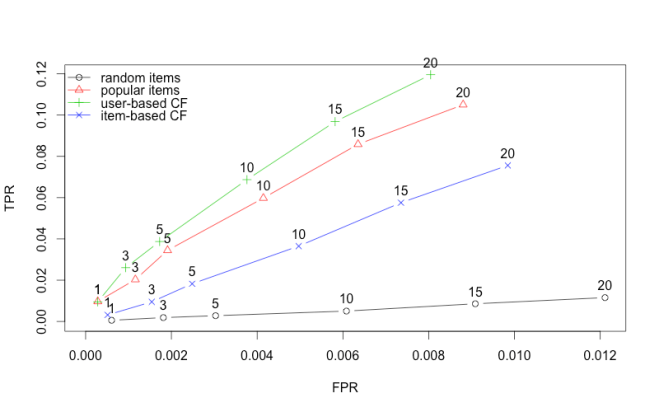

| results <- evaluate(scheme, algorithms, n=c(1, 3, 5, 10, 15, 20)) | |

| # Draw ROC curve | |

| plot(results, annotate = 1:4, legend="topleft") | |

| # See precision / recall | |

| plot(results, "prec/rec", annotate=3) |

It seems like UBCF did better than IBCF. Then why would you use IBCF? The answer lies is when and how are you generating recommendations. UBCF saves the whole matrix and then generates the recommendation at predict by finding the closest user. IBCF saves only k closest items in the matrix and doesn’t have to save everything. It is pre-calculated and predict simply reads off the closest items.

Predictably, RANDOM is the worst but perhaps surprisingly it seems, its hard to beat POPULAR. I guess we are not so different, you and I.

In the next post I will go over some other algorithms that are out there and how to use them in R. I would also recommend reading Michael’s documentation on recommenderlab for more details.

Also added this to r-bloggers. Please check it out for more R goodies.